Chordal

Guitar Intro

When we listen to music, the first things we usually hear are the melody, the beat, or the lyrics. What's also present throughout almost all kinds of music is a harmonic language. This language is much simpler than a spoken language, often using only a few common chords.

Being aware of and fluent in this harmonic language is an essential part of playing and understanding popular music. Most beginner musicians learn songs through the aid of chord charts, online tutorials, or sheet music. Even some intermediate and professional musicians are dependent on learning this way. These methods temporarily work but only focus on the 'what' and not the 'why' of music. Chordal offers a more streamlined way to learn this language by always teaching music in context.

This harmonic language focuses on recognizing chords by their sound within a key. Most people are already able to do this with individual notes. For example, chances are you can recognize the correct pitch of ‘Happy Birthday’ if given a starting chord, or recognize if someone is in or out of key while singing something like The National Anthem. The chords under those notes act in the same way. The only difference is that melody happens in the foreground; everyone can easily hear it. Chords happen in the background and serve as a foundation for melody and music as a whole; recognizing their sound and distance takes a bit of practice. This is where numbers come in.

How Numbers Work

Chords always have a home together in a musical key. A key is an exclusive group of notes and chords that sound good and work predictably together. In order to see the relationship between these chords, we need to put them in order in the music alphabet and number them.

The musical alphabet consists of the notes:

A, B, C, D, E, F, and G

There are five additional notes referred to as sharps(#) or flats (b), their names changing depending on context. These 12 total pitches are all the possible notes names of tones in Western music.

A, A#/Bb, B, C, C#/Db, D, D#/Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, G#/Ab

Though the sharp and flat notes can go by two different names, they are the exact same pitch. Viewed on piano, these notes really come into focus.

The 12 pitches in music. There are two instances of no #/b note; between B/C and E/F.

Out of these 12 notes, 7 come together to form a major scale (Do, Re, Mi...), the backbone of our harmonic language and central players in a musical key. The simplest major scale to understand is the C major scale: the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C (the white keys on a piano from C-C). To work with major scales, we attach numbers to each note.

C-1 D-2 E-3 F-4 G-5 A-6 B-7

A key not only includes the major scale notes, but also chords built off each scale note. The most common chords used in music include chords built off the 1, 4, 5, and 6. The chords built off of 1, 4, and 5 (C, F, G) are major. The 6 chord is naturally minor (Am)*. A great walkthrough of the above concept can be found here. There are less common chords built off of the 2nd, 3rd, and 7th notes of the scale that will be covered down the road.

*Why the 6 chord is naturally minor will be covered later on.

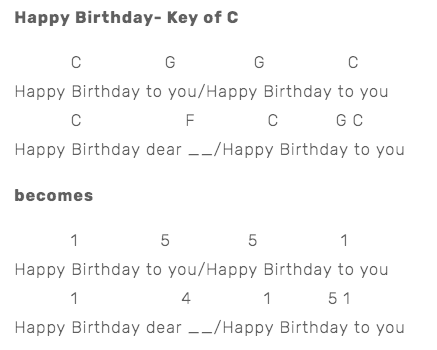

The bulk of this site is made up of charts that replace chords of popular songs with their corresponding numbers in a key. Here is an example in the key of C:

Why Numbers Work

The 1, 4, 5, and 6m chords have come to represent sounds that are essential to popular music. C, F, G, and Am are simple to play on piano and guitar, and any ordering of these chords should sound familiar. In fact, thousands of songs have been written with just those four chords. There is nothing special about those particular chords. What makes these chords work so well is the distance between them and how they sound and function in a musical key. These chords operate very much like a language. Using numbers in place of chords makes it possible to highlight and learn this aspect of music.

Of course, there are countless songs that use other sets of chords from other keys. Just like there are many languages, there are several musical keys that songs are written in (12 keys to be exact*). This means that there are 12 unique major scales, and 12 unique groupings of 1, 4, 5, and 6m built off of those scales. The key of a song depends on a few factors (what a vocalist prefers, which key inspiration struck, which instrument was used to write a song, etc). So depending on the key, our numbers could be defined 12 different ways. In C, C is 1, but in the key of G (where G is 1) C is a 4 chord. In the key of F (where F is 1), C is a 5 chord. Switching fluently between keys and keeping track of which number is what is an impossible task for a beginner. Chordal charts make this concept accessible by only focusing on one key and one set of numbers as long as it takes for it to become effortless.

*There are a few ways to answer “How many musical keys are there?” but for popular music and the vast majority of purposes, 12 is a sufficient answer.

Because songs are constantly played in different keys, and all those keys have different sets of chords, it might seem pointless to further complicate things and add another step by replacing chords with numbers. What makes numbers actually easier in the long run to think in is that numbers sound the same in any key, on any instrument, and in any style of music.

Let that sink in.

The 1, 4, 5, and 6m chords (and all other chords), no matter what kind of music or instrument, will relatively sound the same in every musical key. This is why it’s possible to transpose the same song in different keys and for it to retain the same sound (only sounding higher or lower). When changing keys, the actual chords change; the numbers stay the same. What makes music sound a certain way aren’t the specific notes but the distance and relation between them.

The incredible commonality of these 4 particular chords can’t be overstated- chances are if you turn on the radio or pull up Spotify or Pandora and play a song at random, it’s these four chords working together in a key. There is plenty of music where the chords are much more complex and unrelated, jumping outside of keys and easily confusing the ear. The vast majority of popular music, however, isn’t this way. If there is more than 1, 4, 5, and 6m to a chord progression, chances are those chords are still heavily involved. Keeping this probability in mind greatly simplifies learning new music and playing by ear. Could there be 20 chords in this song? Chances are there are only 4 or so. Are the chords totally randomly chosen? Probably not, they belong in a key together and probably act as a combo and ordering of either 1, 4, 5, or 6m. Thinking in numbers trains our ear to recognize a handful of sounds instead of thousand.

Similar to a synonym, the same chord can vary in its specific sound, timbre, and texture. These differences are due to many factors: the instrument, the genre of music, the rhythm of the chord, or the voicing (the specific way the chord is constructed).. Though these differences can at first be a distraction, numbers orient the ear to hear the underlying progression.

A good example of the prevalence of these 4 chords can be found in this viral video that jokingly (but rather accurately) reveals that many well-known songs have the same chord progression. Though those songs partially do share chord progressions (meaning they have the same numbers), they all are actually in different keys. By transposing them into the same key, the fact that they share the same chords is easy to hear. With training, even songs that share progressions but are in different keys can sound incredibly similar.*

*Sometimes too legally similar- the similarities between Lana Del Rey’s Get Free, Radiohead’s Creep, and The Hollie’s The Air That I Breathe caused various legal copyright infringement battles between the artists over the years. The issue wasn’t a stolen melody but that the chord progression (numbers) and overall feel of the songs bore a striking resemblance to one another.

This is why using numbers instead of chords gets to the heart of how music sounds and why it works. The actual notes and chords (like the physical words and letters used in a language) don’t matter too much by themselves. The meaning comes from thinking in context of a key, and numbers highlight this context in a way that chords and even sheet music just don’t.

The most cited benefit of numbers is that it easily facilitates transposing a song into other keys, which is true (and immensely useful). But thinking in numbers represents so much more than that. Imagine you could fluently and effortlessly speak all the world’s major languages. Because of this incredible skill, you constantly travel around the world doing interviews and giving speeches, instantly adapting your meaning of what you wanted to communicate to the particular language you encounter. This is what it’s like to be fluent in numbers in music. Enough work with numbers and it’s possible to pick out the chord progression immediately for a song heard on the radio, in the grocery store, in a band rehearsal - anywhere and at any time.

Like learning a language, remember, attaining fluency with one key and one set of numbers is really the only way to learn this concept. Because numbers sound the same in every key, practice in even one key is immediately and permanently beneficial. This is where the guitar comes into play. Though C chords (C, F, G, and Am) are good for guitar, Chordal guitar charts focus on the reading numbers in G first. G chords are even simpler and more commonly played than C chords.

Because we will be dealing with the key of G, our chords will change. 1, 4, 5, and 6m in the key of C are C, F, G, and Am . Now that we're in the key of G, our major scale is entirely different.

G-1 A-2 B-3 C-4 D-5 E-6 F#*-7

1, 4, 5, and 6m are now (in G) G, C, D, and Em.

*Why the F is sharp in the key of G will become clear as we learn the way a major scale is built.

G, C, D, and Em (In G), and C, F, G, and Am (In C), are essentially two different ways of musically saying the same thing. A song written with G chords (a bunch of G, C, D, and Em, in no particular order, for 3 minutes) could easily be transposed to C (a bunch of the equivalent 1, 4, 5, and 6m in the key of C) and it would sound relatively the same. The only difference would be it sounding lower or higher, usually depending on the vocals. By using numbers, a musician gets to the musical point quicker by training their ear to recognize numbers and putting them in whatever key is needed.

Now that we know the first words of our language, our goal is immersion- using our numbered chords in G (1, 4, 5, and 6m) to play hundreds of songs in every style and period of music. This will make your musical ear stronger and make learning and playing music simpler and more enjoyable. In practice, numbers look like this:

Happy Birthday- Key of G

G D D G

Happy Birthday to You / Happy Birthday to You

G C G D G

Happy Birthday Dear __ / Happy Birthday to You

becomes:

1 5 5 1

Happy Birthday to You / Happy Birthday to You

1 4 1 5 1

Happy Birthday Dear __ / Happy Birthday to You

Because music is usually grouped in sets of 4 beats to a chord and keeps steady time, we don’t even need the lyrics. Slashes (/) simply break up the music into 4 measure groups. Try to follow along with the linked recording of Brown Eyed Girl with the below numbers, and see if you meet up with the "you, my brown eyed girl" on the bolded 4 chord (C).

Brown Eyed Girl, Van Morrison (Key of G)

Intro- 1 4 1 5 / 1 4 1 5

Verse- 1 4 1 5 / 1 4 1 5 / 1 4 1 5 / 1 4 1 5

Pre- "You" 4 5 1 6m / 4 5 1 5

One more example:

Leaving On A Jet Plane, John Denver (Key of G)

Whole Tune- ||: 1 4 1 4 / 1 4 5 5 :||

( The double bars and dots mean to repeat)

More song examples written in a similar way can be found on the Simple Song Charts page.

This turns out to be the simplest way to learn chords to most songs. The added benefit is that we are actively speaking a harmonic language and becoming fluent in hearing and understanding music. Millions of professional musicians, amateurs, hobbyists, composers, and others with a developed musical ear perceive music in this way because it gets to the heart of understanding the harmony and connectedness that links everything we hear.

An indispensable tool for learning songs with numbers is a capo, a clamping device for the fretboard that transposes easy, resonant chords to sound higher and in a different key. Beginner Chordal charts often call for the use of a capo because songs are often in keys other than G.

Using a capo accomplishes three things:

7 or so of the 12 keys in music aren't great for strumming chords and generally don't sound open or resonant. Capoing enables us to play a song that's not in a guitar-friendly key with easier and better chord forms.

Many acoustic artists utilize a capo to change the key, raising the guitar up for their vocals. Learning and playing along with recordings of these songs obviously requires a capo to reproduce the same sound. Similarly, if a song is too low or high and you accompany yourself or someone else on guitar, a capo is a great way to effortlessly change the key by moving the capo up or down a fret or two.

Thirdly (and most importantly), moving around one set of chords means you get more practice with one set of numbers, and that’s the first mission with using our musical language: fluency that comes from thinking in and hearing one set of numbers with real world examples.

The Charts

Chordal guitar charts are organized by key forms (or a group of chords from a key that are great for guitar). In each key form’s subgroup, charts are organized by the amount chords they contain, then genre, then difficulty.

G Form charts are all found together. In this main group, the 4 chord section of charts contain only 1, 4, 5, and 6m in either the key of G, or a key that we can capo the key of G to sound like. These charts don’t necessarily always have 4 chords- they can contain any iteration of 1,4,5, and 6m, often even just 3 total chords (1, 4, and 5 or 1, 4, and 6m for example).

The 5 chord section contains charts with those 4 chords, plus the 2m (Am) (and any iteration of those 5 chords), with similar mixed keys.

Finally, 6+ chord charts can contain any amount of chords both in and out of the key of G, but still are all able to be played in G form.

On each page charts are grouped together by genre and a general difficulty level within that genre. The 4 and 5 chords charts often have very little learning curve. The 6+ chord charts will take practice, study, and patience. Being able to make sense of a difficult number chart indicates a history of living with and practicing these concepts regularly.

Of course, the guitar is played in other keys besides G (even considering the capo). A song in a D form or C form has a different but equally necessary personality than the key of G (see the capo section for an in-depth explanation of this). After G numbers are mastered, these other great key forms for guitar are too explored thinking in numbers.

The below Resources links are essential reading before any charts:

How to Read Charts

Song Sections and Forms

Simple Song Charts

How to Capo the Guitar